I taught my students about outer space last month. We learned many facts about planets, stars, and more. But while science education for young children often emphasizes the factual knowledge, I want my students to do more than regurgitate. I want to foster an early understanding of scientific methods, because it’s not the products but the processes that set science apart.

When we talk about science, I often remind my students that scientists try to learn new things. That means they come up ideas—hypotheses—that might be wrong. Sometimes, scientists must change what they think.

Pluto offers a nice example. Every year, a few students enthusiastically declare that Pluto is no longer a planet. But if I ask follow up questions, they usually reveal that they think Pluto changed in some way—that it was a planet until something happened to it. Of course, the only thing that changed is in our heads. Scientists used their instruments to learn more, and that changed how they think about Pluto.

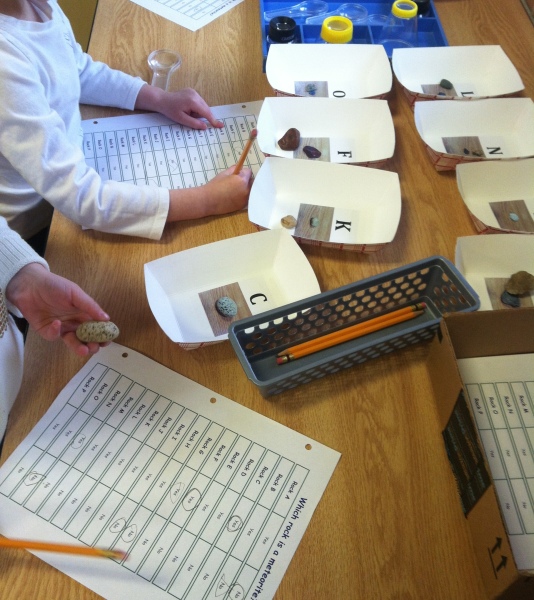

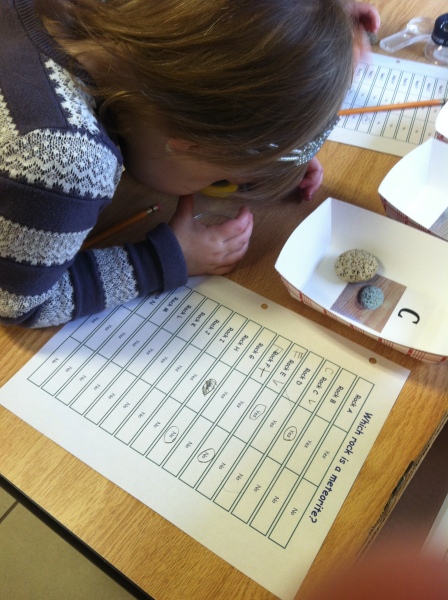

To give my students practice making their own hypotheses and changing what they think, I set up an activity with meteorites. I put out sixteen rocks and told them that some had come from outer space and crashed into the earth. I challenged them to come up ideas about which ones were from outer space. They weighed the rocks with our scale, and looked at them with various magnifying glasses. I asked many open-ended questions to flush out students’ reasoning.

A handful of hypotheses emerged. Some students thought that meteorite must have “holes” (craters) like the Moon and Mercury. Some thought that the meteorites would have to be a certain color, perhaps black. Some looked for scratches caused by crashing into the earth. And some students were more vague, saying things like, “I just think it looks like a space rock.”

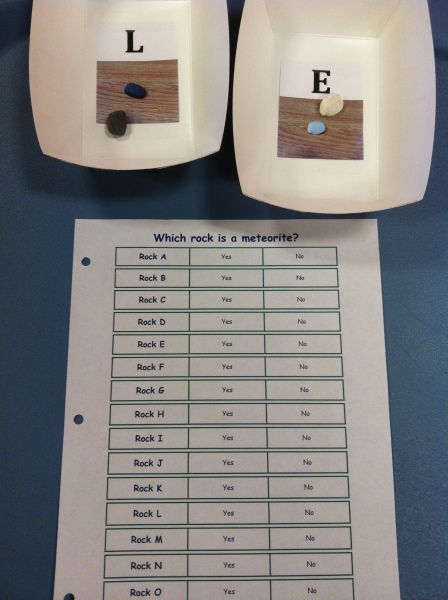

On the third day, I asked students to start recording their ideas on a chart. Each rock had been assigned a letter. Students circled ‘yes’ or ‘no’ for whether they thought each rock was a meteorite. On subsequent days, I reminded them that they might want to change what they think, and many did.

When I was ready to wrap things up, we sat down to have a summary discussion. We began by making a graph that represented how many students thought each rock was from outer space. There was some consensus, but much disagreement.

Then I pulled out my computer and together with the class did some (staged) research on what meteorite scientists have learned, because they have looked at many more rocks than we have, and they have done experiments on them. We learned two pieces of useful information. First, meteorites are heavier than most rocks of the same size. Our rocks varied in size and some of our small rocks weighed little enough that they wouldn’t register on our scale, so to avoid confusion I moved on. Second, because meteorites have iron in them, they will stick to strong magnets. We pulled out some strong magnets and tested each rock. We found two that were magnetic. (They are, in fact, meteorites; I purchased them here.)

Now, I don’t really care if my students learned that meteorites are magnetic. That wasn’t my goal, so I didn’t stress that point. Instead, I emphasized the way new information had changed what we think. I asked, “What did you think before? What do you think now? Have you changed your mind?” One or two students maintained their previous positions. If they were scientists, I told them, they would need to learn more about meteorites. Then maybe they could make the rest of us change what we think again.