This past summer, I introduced my class to a series of science activities using mealworms. I had expected it would capture my students’ interests for just a few weeks, but it developed into a deep investigation, which captivated us for most of the summer. I’d like to describe some of what unfolded.

First, a few tips. Mealworms are easy to care for. You can buy them at most pet stores—they’re meant as food for pet reptiles, and they’re usually stored in a refrigerator until they’re sold. They can eat a variety of foods (including polystyrene, apparently), but I recommend oat bran, because it serves well as both bedding and food. The only other thing they need is water, which they can pull from fresh vegetables. I used baby carrots, because they’re cheap, easy, and long lasting.

An Introduction

Before introducing my mealworms to the class, I let them grow fairly large—about an inch long. I hoped students wouldn’t have to wait long before seeing changes.

I didn’t tell the children what was going to happen. In fact, I didn’t even use the word ‘mealworm’ at first. Instead, we began by discussing larvae. I asked what they knew about caterpillars and butterflies (which was plenty). I pointed out that a caterpillar is one kind of larva—that there are many other types of insects that begin as larvae before changing.

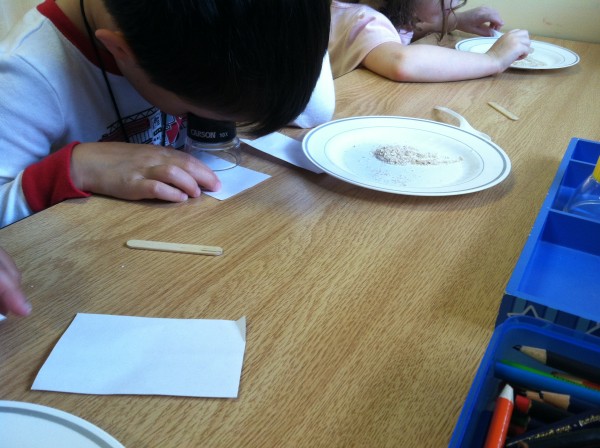

Then, I pulled out the mealworms (“larvae,” I called them) and we started observing. I scooped them out of the terrarium and onto plates for closer inspection.

I asked children to speculate on what kinds of insects our larvae might turn into. Hypotheses included: butterflies, beetles, ants, bees, and flies. One student suggested that I get a lid for the terrarium, because he expected the larvae to change into flies.

Metamorphosis

Soon, we began to see changes. There was dead skin in the terrarium, evidence that larvae had been shedding their skin. We also noticed the appearance of small, half-curled little critters that moved very little, if at all. I suggested that some larva might have turned into pupae—the transitional stage between larva and adult insect. (A caterpillar’s chrysalis is a pupa, too, I pointed out.)

About a week later, we saw our first beetles. The beetles were white at first, making them difficult to spot in with the oat bran, but they slowly changed to brown or black.

Studying Individuals

At this point, the children were very excited. I wanted to find a way to extend our study. We hadn’t yet been able to study individual larvae, because they were unidentifiable and they moved around in the terrarium. So I decided to have each student care for a single larva, giving them a chance to observe their own mealworm’s development over time. I punched holes in the lids of small plastic containers. Children prepared their containers with oat bran and carrots, and then they each chose a larva from the terrarium. They named their new pet mealworms. (This was near the height of the Frozen craze; naturally, a full quarter of our mealworms were named Elsa.)

For the following two weeks, children checked on their mealworms daily. They made (mostly rough) drawings of the mealworms each day.

In that two-week period of time, most of the mealworms progressed from larva to pupa to beetle. When students asked to take their larvae, pupae, and beetles out of their containers, I tentatively consented, emphasizing the need for kindness and delicate care when handling live animals. There were some accidental drops, and children weren’t always gentle. (They discovered that they could get pupae to move by “tickling” them.) But the mealworms proved resilient. None of them escaped, all but one continued developing, and we had a lot of fun playing with them.

A New Generation

By this time, our original terrarium had produced twenty or thirty full-grown beetles. After each had emerged from its pupa, I had moved it into a second terrarium. Now, I presented children with a new possibility: perhaps the adult beetles (in the second terrarium) had laid eggs.

I scooped piles of oat bran from the second terrarium onto plates and the children set about looking for eggs. Although we never found anything that looked like an egg, our failure prompted a variety of thoughtful explanations from students: perhaps the beetles hadn’t yet laid eggs; perhaps the eggs were too small to see; perhaps the eggs were camouflaged. One student, drawing from prior lessons on mammals, suggested that beetles might not lay eggs. “Maybe they’re mammals,” she posited.

However, after more careful observation, we did find a fresh set of tiny mealworms! They weren’t easy to spot, but after patiently watching piles of oat bran, we often noticed very slight movements. With careful digging, we were able to locate and isolate these new larvae. My students were so enthralled with searching for these tiny critters that we continued hunting for nearly two weeks.

If you’re looking for a science activity to try with young children, I recommend getting mealworms. They’re cheap, easy, and fun. And with the right guidance, they can present great opportunities to practice thoughtful, creative, early scientific thinking.