We recently had a visitor in our classroom. Emily Conover is a physicist and science writer who earned her Ph.D. in high energy physics. She offered to teach my students a little bit about particle physics and to set up an exciting experiment for our new science center.

I talk to my students about scientists frequently. Whenever there’s an opportunity, I ask them to think like a scientist. Sometimes I wonder if they ever ask themselves, “Why does Joe talk about scientists so much? Can’t he just answer our yes-or-no questions?”

I also wonder what our youngsters picture when I start talking about a scientist. Is it something vague? Is it a man with glasses, pouring liquids into beakers? Having a real life scientist in our classroom gave us a better idea of what a scientist can be like. Emily shared some photographs of some of the instruments she helped build, and of the laboratory in Chooz, France where her experiment is carried out.

Particles and Electrons

Emily also taught us about particles. We learned that everything is made up of very tiny things, much too small to see. Bigger things you can break apart. We can break a cookie, for example, into smaller and smaller pieces. But when it’s as small as a particle, you can’t break it up anymore. That lesson was pretty abstract for our youngsters, but it was a nice introduction.

Next, she taught us about one particle called the electron, which sounds a lot like the words ‘electric’ and ‘electricity’ because when we use electricity, we send tiny electrons through wires.

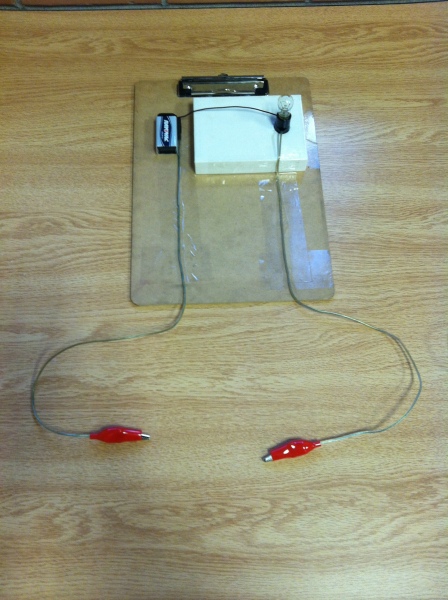

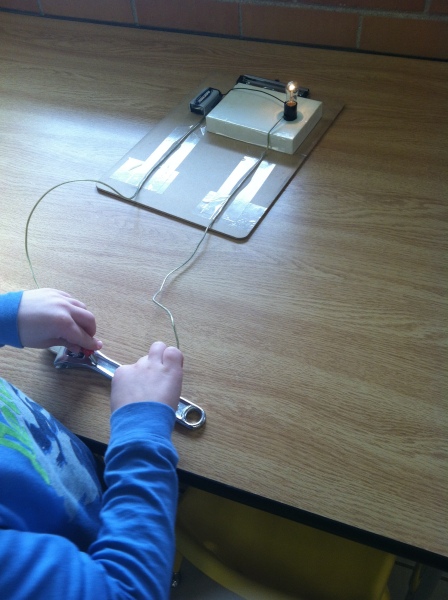

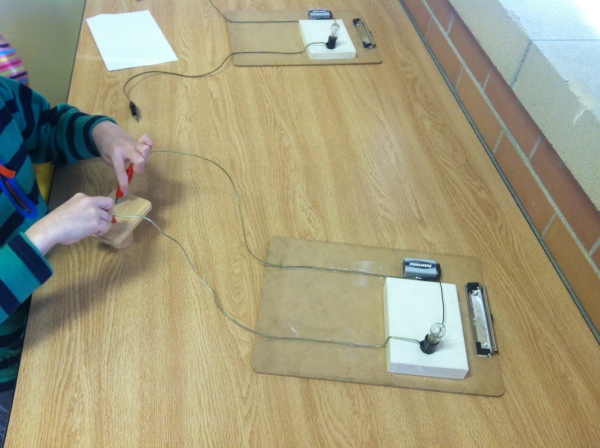

Knowing that electrons can go through wires, we asked the scientific question: what else can electrons travel through? To test it, Emily and I set up a small light bulb, attached to a nine-volt battery, with a break in the wire. We explained that the light bulb would only turn on if the electrons from the battery could go all the way around to the light bulb.

Note: we took a minute at this point to talk about safety. We certainly don’t want children going home and playing with wires. We explained that electricity is very dangerous; our experiment was safe only because we used very small batteries.

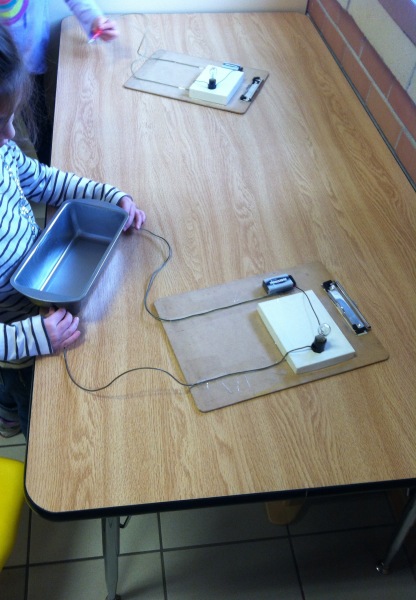

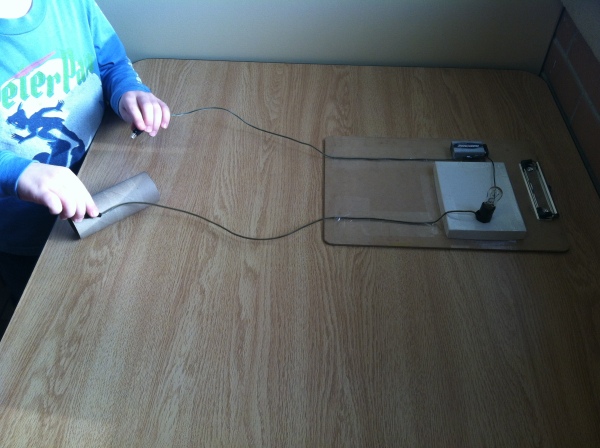

We then set the children loose in our science center and let them experiment, sending electrons into each object and checking to see if they made it all the way to the light bulb. I set out a variety of objects—different shapes, sizes, and materials—and I invited the children to pick other classroom objects or toys to try.

In a matter of minutes, a group of students had discovered that metal seemed to be key. Word spread quickly among the rest of the class, but everyone was eager to test it out nonetheless.

A few metal objects did not work: a non-stick pan and some metal objects with paint on them. They offered opportunities to reevaluate our assumptions, which is the type of thinking I aim to facilitate. Scientists often must change what they think, as I regularly remind my students.

One student was particularly interested in seeing whether electrons could travel through a chain of objects.

We purchased most of the materials that we needed at RadioShack. It took some time to put things together, but it was fun. I’ll hang on to them and use them again in coming years.

I want to thank Emily for thinking of an excellent idea, for carrying it out beautifully, and for taking the time to visit us. My students were lucky to have you.

What did Emily Conover offer to teach the students in the classroom?

Visit us PJJ Informatika