My classroom got some new pets this year. We adopted a group of harvester ants, which gave me the opportunity to teach an extended lesson in scientific experimentation.

Science lessons for young children typically emphasize observation and investigation. That’s a major component of my approach, but I also run experiments with my students on a regular basis. Ants turned out to be great subjects for us to study.

Setting Things Up

I took some time to read about what others had done, and I looked at some products that are available. The first challenge was finding a home for the ants. There are many ant farms available for purchase. Most, if not all, are tall and narrow–designed to demonstrate how ants dig their tunnels. I did want my students to see the ants tunneling, but I also wanted a flat surface on which we could set up experiments. I decided to buy an 8″ by 6″ rectangular plastic food storage container.

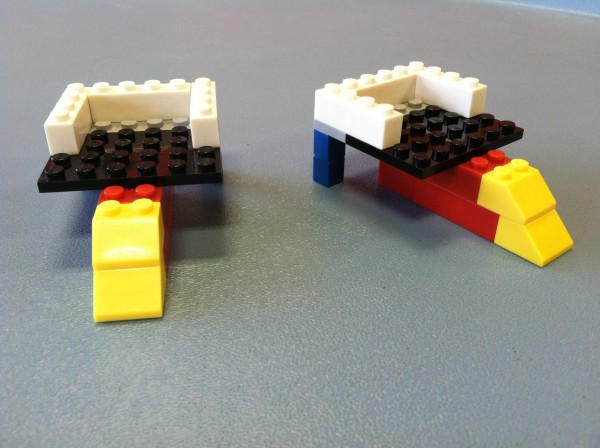

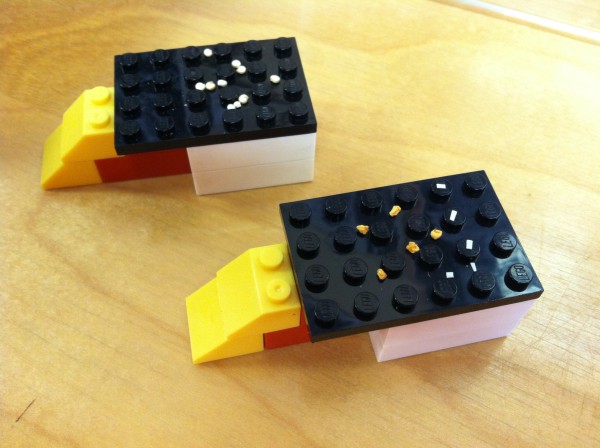

However, there’s a problem with having a wide container. The ants will dig down to center and out of sight if they can. I needed something to keep the ants from digging anywhere but at the edges of the container, where we could see their tunnels. I couldn’t find anything that was quite right, so I did what any of my wonderfully resourceful students would have done; I built something out of Legos.

Next, I needed to get some dirt. I had read that a mixture of dirt and sand works well. I pulled some dirt out of the local garden, mixed it with sand, and then filled my container. Unfortunately, my dirt mixture turned out to be a minor failure. Our ants had a hard time keeping their tunnels from collapsing. We witnessed a few fascinating ant rescue operations. (Tip: don’t try to help; you’ll only make it worse.) The children were pretty empathetic towards those trapped ants, which in retrospect I realized might have been a valuable experience. Perhaps that empathy generalized to some other creatures… or classmates! As for the soil, I don’t know what would have worked better, but I used the opportunity to discuss with my students what we might want to do differently next time. Science doesn’t need to be perfect. (Nor do teachers!) It’s always worth the time to model working through challenges and setbacks and to practice doing so with children as partners.

Then came the key component: ants. I considered getting some from the ground outside. It would be a fun experience finding them as a group. Unfortunately, our school is in the heart of the concrete jungle. Our playground is indoors, as the nearest park is far away. Another challenge would be finding the right kind of ants. I worried that I would end up with escapist ants, nasty biters, or both. Feeling that there were already enough question marks surrounding the project, I decided to purchase red harvester ants from here. They are capable of painful biting, but they are bad climbers, incapable of crawling up the wall of my container. They’re also very active tunnelers. They were delivered ahead of schedule, so I kept them in the refrigerator for an extra day. When I released them, all but a few gradually awoke.

Finally, I had to come up with a way to keep my ants in the dark and hydrated. I was preventing them from digging down into dark places, as is their instinct, so I kept them covered with a dark blanket for most of the day. I also read that providing ants with a source of water was important, but that pools of water were likely to drown them. So we placed small pieces of wet cotton balls in the container with the ants.

Experimentation Begins

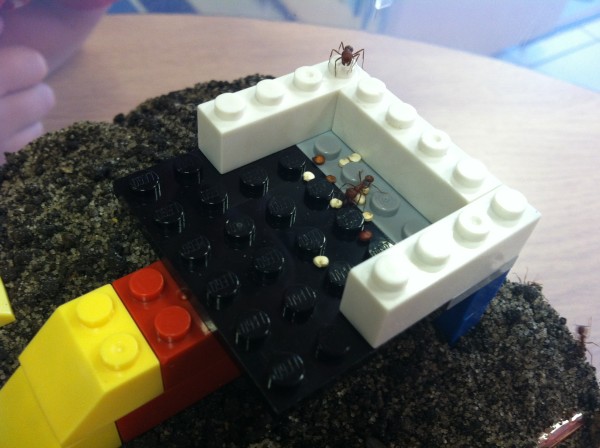

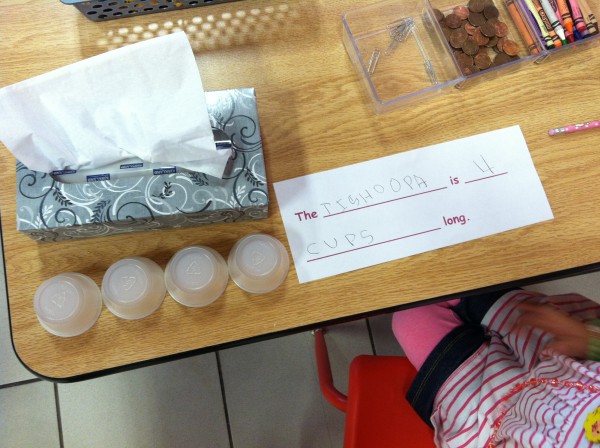

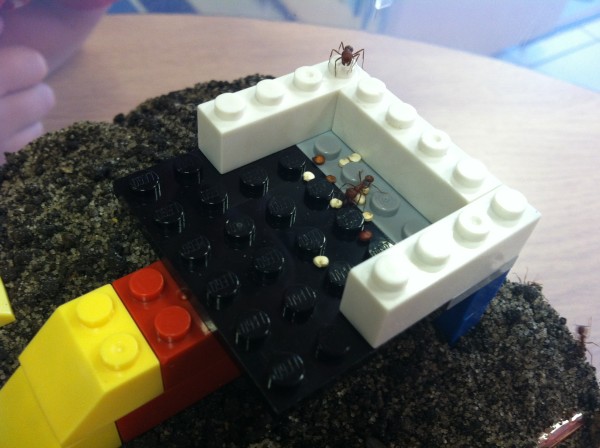

The first few days after releasing the ants, we merely observed them. We talked about observation being a big part of what scientists do–especially animal scientists. You can learn a lot just by watching. Our ants began tunneling almost immediately. Within a day, they had tunnels on two of the four sides of the container. Somehow, they knew not to bother digging in the center of the container. They went straight for the edges. It was fascinating watching the ants carry clumps of dirt around. It’s impressive how much dirt they’re able to move in short periods of time. The children (and I, too) spent many minutes watching and pointing and saying things like “Whoa!” and “Look!”

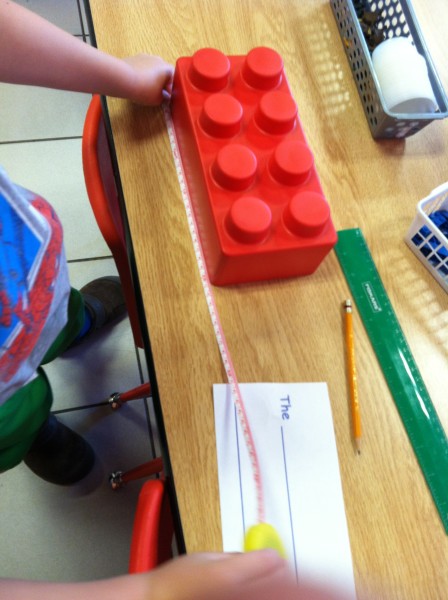

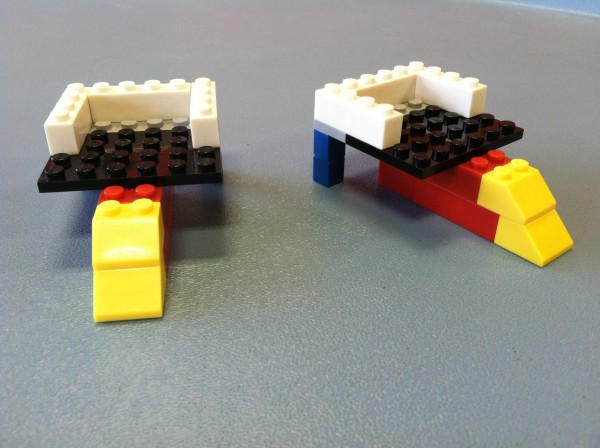

Then we started setting up simple experiments. I used Legos again to make little feeders that we could put different foods on. I put food on the feeders and carefully placed them on the flat surface in the middle of the container. We wanted to see which foods the ants would prefer. Over the course of weeks, we tried comparing many foods: strawberries, quinoa, corn meal, barley, blueberries, graham crackers, chia seeds, pineapple, garlic, rice, and more. With some combinations, it was difficult to determine whether there was a preference. Other times, it seemed clear what the ants preferred. Strawberries always drew a crowd of ants. Tiny pieces of blueberries and graham cracker crumbs were carried off quickly. Quinoa was perhaps our favorite to watch; because of its light color, it was easy to see when and where the ants carried it.

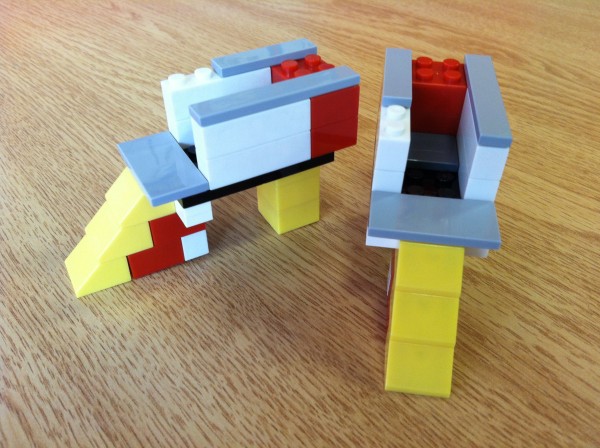

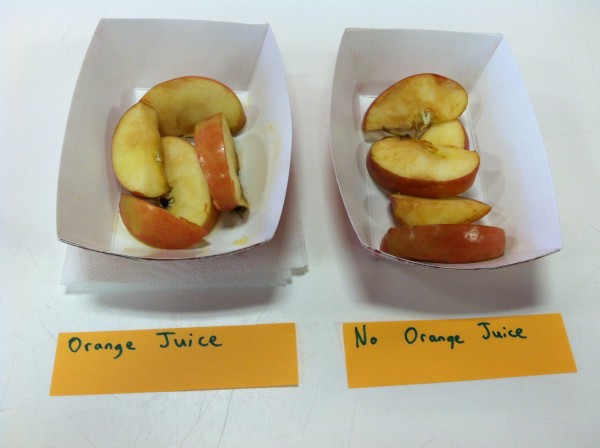

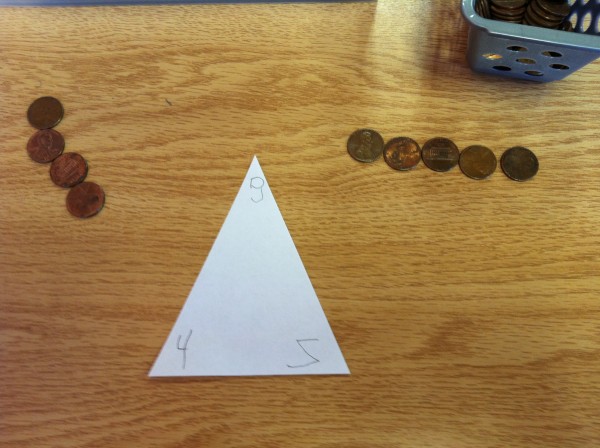

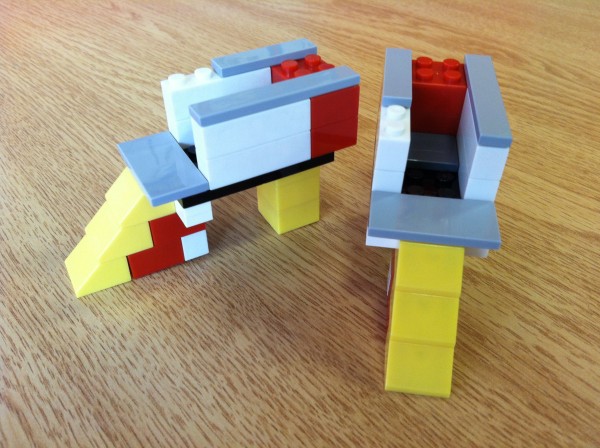

In another experiment, we set out to test whether ants will avoid cinnamon. I built taller feeders that forced the ants to cross over a small indentation. In that space, one feeder had nothing, while the other was filled with cinnamon powder. We left quinoa and blueberry pieces on both feeders beyond the indentation.

The results were clear. We watched the ants crawling in and out of the feeder without cinnamon, and all of its food was gone within days. In contrast, the feeder with cinnamon seemed to be untouched; even after a week, all of its food remained in place.

This particular experiment was rewarding for me as a teacher. Things seemed to click; the kids really seemed to understand how this experiment helped us learn about our ants. With earlier experiments, I often asked somewhat leading questions to help the children understand what the experiments had taught us. This time, all I had to say was, “What do you think?” and the kids did the deductive reasoning on their own.

In preparation for another experiment, we talked about why the ants didn’t cross the cinnamon. Perhaps it was the odor, or perhaps it was the way it feels. I suggested that maybe ants don’t like walking on any kind of powder. So, we tried the exact same experiment but with ginger powder. This time, the food disappeared from both feeders. In fact, the ants seemed to have done some digging in the ginger powder.

After a month or so of experimenting, I began to wonder about some ant behaviors. It was often hard to tell what the ants were doing. We had to do a lot of guessing. One question in particular I wanted to investigate.

Most of the foods that we left out were carried to one or two corners of the container. The ants seemed to be storing it, but we weren’t sure. Perhaps ants like to carry things around and pile them up. Perhaps some, if not many, of the foods that were carried off of our feeders weren’t actually eaten.

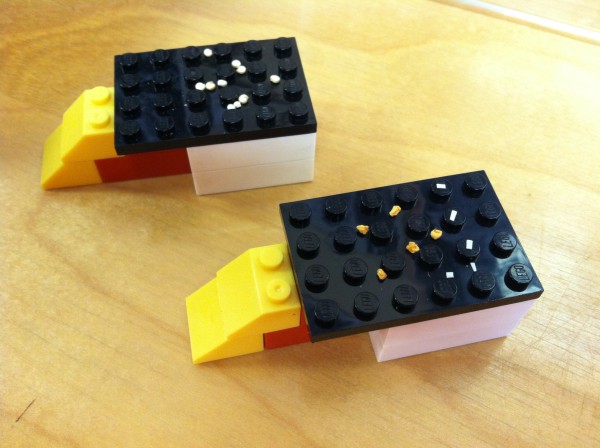

To test these possibilities, I set up two new feeders: one with quinoa, one with tiny pieces of orange paper and white plastic. To our surprise, the ants carried everything away, calling into question the validity of our previous food comparison experiments. We may have been testing a preference for what ants like to carry, not a preference for what ants like to eat.

However, if I could start over, I may not do things differently. I had hoped to demonstrate the many ways scientists tinker with their experiments and question their assumptions. Finding a big problem with the validity of our previous experiments gave us a chance to talk about the ways science can stumble in its slow journey toward new knowledge.

As a whole, the project was a little crude, but fairly scientific, too. I think it did a lot to help give my young students a good early foundational understanding of how science works.